Table of Contents

Geographic Space

Geographical networks: geographical effects on network properties

| Kong-qing YANG, Lei YANG, Bai-hua GONG, Zhong-cai LIN, Hong-sheng HE, Liang HUANG | 2008 | Frontiers of Physics in China, 3(1): 105―111 |

Abstract: Complex networks describe a wide range of systems in nature and society. Since most real systems exist in certain physical space and the distance between the nodes has influence on the connections, it is helpful to study geographical complex networks and to investigate how the geographical constrains on the connections affect the network properties. In this paper, we briefly review our recent progress on geographical complex networks with respect of statistics, modelling, robustness, and synchronizability. It has been shown that the geographical constrains tend to make the network less robust and less synchronizable. Synchronization on random networks and clustered networks is also studied.

The Spatial Structure of Networks

| M. T. Gastner and M. E. J. Newmann | 2006 | The European Physical Journal B, 49: 247-252 |

Abstract: We study networks that connect points in geographic space, such as transportation networks and the Internet. We find that there are strong signatures in these networks of topography and use patterns, giving the networks shapes that are quite distinct from one another and from non-geographic networks. We offer an explanation of these differences in terms of the costs and benefits of transportation and communication, and give a simple model based on Monte Carlo optimization of these costs and benefits that reproduces well the qualitative features of the networks studied.

Internet and airline networks are not really two-dimensional at all, but the road network is.

| Internet | airlines | highway | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vertices | 7049 computers | 187 airports | 935 intersections, termination points, and country borders |

| edges | 13831 links | 825 scheduled flights | 1337 highway stretches |

| diameter | 8 | 3 | 61 |

| degree of the vertices | 2138 (30%) | 141 (76%) | 4 (0,4%) |

| peaks on the distribution | two | two | one |

Why do not use cities as vertices of a highway instead of intersections, termination points and country borders?

Future work: the effects of population distribution on the networks, and vice-versa.

Geographic routing in social networks

| D. Liben-Nowel, J. Novak, R. Kumar, P. Raghavan and A. Tomkins | 2005 | PNAS, 102(33): 11623–11628 |

Abstract: We live in a ‘‘small world,’’ where two arbitrary people are likely connected by a short chain of intermediate friends. With scant information about a target individual, people can successively forward a message along such a chain. Experimental studies have verified this property in real social networks, and theoretical models have been advanced to explain it. However, existing theoretical models have not been shown to capture behavior in real-world social networks. Here, we introduce a richer model relating geography and social-network friendship, in which the probability of befriending a particular person is inversely proportional to the number of closer people. In a large social network, we show that one-third of the friendships are independent of geography and the remainder exhibit the proposed relationship. Further, we prove analytically that short chains can be discovered in every network exhibiting the relationship.

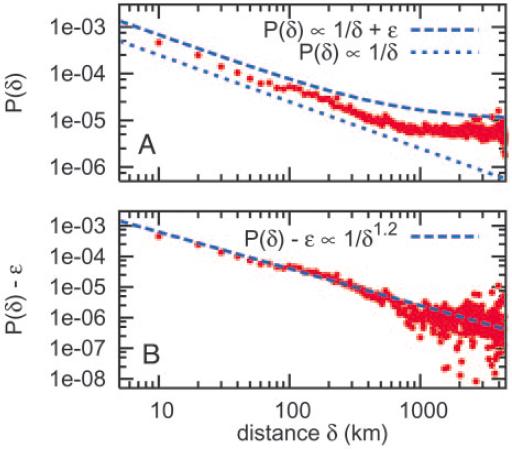

At first blush, geographic location might have very little to do with the identity of a person’s online friends, but Fig. 3A verifies that geography remains crucial in online friendship. Although it has been suggested that the impact of distance is marginalized by communications technology (26), a large body of research shows that proximity remains a critical factor in effective collaboration and that the negative impacts of distance on productivity are only partially mitigated by technology (27). However, for distances larger than 1000 km, the curve approximately flattens to a constant probability of friendship between people, regardless of the geographic distance between them.

Social and Geographic Distance in HIV Risk

| R. Rothenberg, S. Q. Muth, S. Malone, J. J. Potterat and D. E. Woodhouse | 2005 | Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 32(8): 506–512 |

Objective: The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between social distance (measured as the geodesic, or shortest distance, between 2 people in a connected network) and geographic distance (measured as the actual distance between them in kilometers [km]).

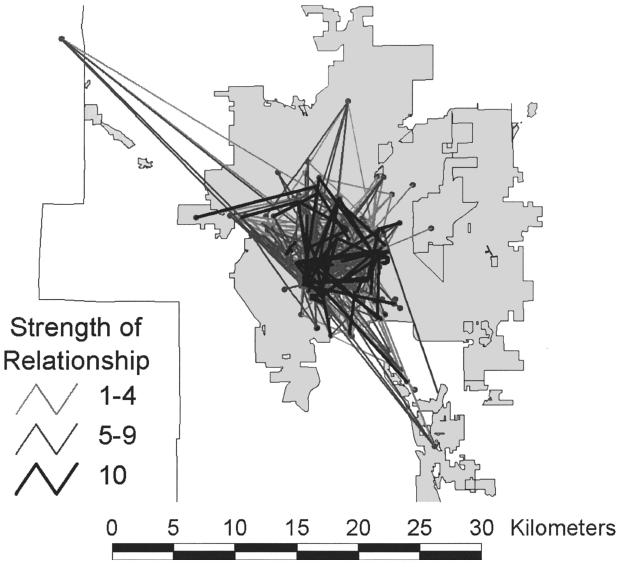

Study: We used data from a study of 595 persons at risk for HIV and their sexual and drug-using partners (total N = 8920 unique individuals) conducted in Colorado Springs, Colorado, from 1988 to 1992—a longitudinal cohort study that ascertained sociodemographic, clinical, behavioral, and network information about participants. We used place of residence as the geographic marker and calculated distance between people grouped by various characteristics of interest.

Results: Fifty-two percent of all dyads were separated by a distance of 4 km or less. The closest pairs were persons who both shared needles and had sexual contact (mean ~ 3.2 km), and HIV-positive persons and their contacts (mean ~ 2.9). The most distant pairs were prostitutes and their paying partners (mean ~ 6.1 km). In a connected subset of 348 respondents, almost half the persons were between 3 and 6 steps from each other in the social network and were separated by a distance of 2 to 8 km. Using block group centroids, the mean distance between all persons in Colorado Springs was 12.4 km compared with a mean distance of 5.4 km between all dyads in this study (P <0.0001). The subgroup of HIV-positive people and their contacts was drawn in real space on a map of Colorado Springs and revealed tight clustering of this group in the downtown area.

Conclusion: The association of social and geographic distance in an urban group of people at risk for HIV provides demonstration of the importance of geographic clustering in the potential transmission of HIV. The proximity of persons connected within a network, but not necessarily known to each other, suggests that a high probability of partner selection from within the group may be an important factor in maintenance of HIV endemicity.

Understanding Spatial Structure from Network Data: Theoretical Considerations and Applications

| G. A. Rabino and S. Occelli | 1996 | Paper presented at the 28th International Geographical Congress |

Abstract: In the past decade, analysis of flow data has been of practical concern in most studies dealing with regionalization and transportation land-use problems. Existing methodologies however show difficulties to cope with the increasing complexity of spatial structures because of the 'variety' of roles which nodes and links are likely to play within the overall interaction structure. By applying graph-theoretic considerations, it is argued that an investigation of both direction and versus of network links can reveal a whole range of spatial 'typologies' .

The first section provides some arguments for a deeper understanding of flow data. It is shown that a conceptualisation of network flows as a result of interacting places defines a general framework according to which a whole range of interaction patterns (e.g. spatial structures) can be recognised. Two empirical applications of these ideas are described in the following sections. Section 3 presents an extension of the dominant-flow approach which is applied to the journey-to- work flows for the Piedmont region over the last three decades. Besides identifying the hierarchical structure, the consideration of the sub-dominant and complementary flows allows to identify a typology of relationships and get a deeper insight in the changes of the regional spatial structure during the 1971-1991 period.

In section 4, an analysis of the residential mobility for the Turin metropolitan area is carried out. By analysing the sub-set of links which have a 'strict complementarity', some 'circuit-like- structures' are revealed which may be also interpreted as interlinked residential market areas.